GPS Accuracy on Phones: Can You Really Survey Land in 2026?

Phone GPS has improved dramatically in the past few years. Dual-frequency chips, multi-constellation tracking, and better processing algorithms have pushed consumer devices into territory that was once reserved for dedicated GPS handhelds. But does that mean you can survey land with your phone?

The short answer: it depends on what you mean by "survey." For a legal boundary survey filed at the county recorder's office, no. For measuring field acreage, planning a fence, estimating landscaping materials, or verifying a property listing, absolutely yes. Let's break down exactly what modern phone GPS can and cannot do, with real numbers.

The State of Phone GPS in 2026

The GPS landscape has changed significantly from even a few years ago. Modern smartphones no longer rely on the single-frequency L1 GPS signals that defined consumer positioning for decades. Here is what your phone is actually working with today.

Dual-frequency reception (L1 + L5). Since roughly 2018 on the Android side and 2020 on Apple's side, flagship phones have included dual-frequency GNSS chips. The L1 signal (1575.42 MHz) is the legacy civilian GPS frequency. The L5 signal (1176.45 MHz) is newer, more robust, and transmits at higher power. By receiving both frequencies simultaneously, your phone can correct for ionospheric delay, which is one of the largest error sources in single-frequency GPS. This alone can cut positioning error by 30-50% in many conditions.

Multi-constellation GNSS. Your phone does not just use American GPS satellites. It simultaneously tracks signals from GLONASS (Russia, 24 satellites), Galileo (EU, 28+ satellites), BeiDou (China, 35+ satellites), and in some regions QZSS (Japan) and NavIC (India). At any given moment, your device might have line-of-sight to 30 or more satellites. More satellites means better geometry, more redundancy, and more reliable fixes, especially in partially obstructed environments.

Assisted GPS (A-GPS) and network corrections. When your phone has a cellular or Wi-Fi connection, it downloads satellite almanac and ephemeris data from network servers rather than waiting to receive it from the satellites themselves. This is why your phone gets a position fix in seconds rather than the 30-60 seconds a cold-start GPS receiver needs. Some devices also receive differential correction data that further refines the position.

The result of all this is that a 2026 smartphone is a genuinely capable GNSS receiver. It is not a survey instrument, but it is far more accurate than most people assume.

How Phone GPS Actually Works

Understanding the basics helps you make sense of accuracy claims and know how to get better results. Here is the simplified version.

Trilateration, not triangulation. GPS positioning is based on distance measurement, not angle measurement. Each satellite broadcasts a signal encoded with its precise position and the exact time it was sent (using onboard atomic clocks). Your phone measures how long each signal took to arrive and multiplies by the speed of light to get a distance. With distances to four or more satellites, the phone can calculate its position in three dimensions (latitude, longitude, and altitude), plus correct for clock error in the phone's own less-precise oscillator.

The math behind the accuracy. Each satellite range measurement has some error. The phone's processor runs a least-squares adjustment (or Kalman filter) that finds the position most consistent with all the measurements simultaneously. The more satellites it can use, and the more spread out they are across the sky, the more precisely it can pin down your location. This is why open sky matters so much: it is not just about signal strength, but about having satellites at different angles.

Sensor fusion. Modern phones do not rely on satellite signals alone. They combine GNSS data with the barometric altimeter (for altitude), accelerometer and gyroscope (for movement detection and dead reckoning), Wi-Fi positioning (using known access point locations), and cell tower triangulation. Apple calls this "sensor fusion." The result is a position estimate that is typically smoother and more stable than raw GNSS alone, especially during brief signal interruptions like walking under a tree.

Real-World Accuracy: What to Expect

Real-world GPS measurement showing accuracy in open terrain

Lab specifications and marketing claims are one thing. Here is what you will actually see in practice when you use a modern smartphone for positioning.

- Open sky, clear conditions: 1 to 3 meters (3 to 10 feet) horizontal accuracy. This is the best-case scenario and what you will get in an open agricultural field, parking lot, or any area with unobstructed sky. Dual-frequency phones consistently hit the lower end of this range.

- Suburban or light tree cover: 3 to 5 meters (10 to 16 feet). Scattered trees or single-story buildings nearby degrade accuracy somewhat, but results are still very usable for land measurement.

- Urban environment with tall buildings: 3 to 8 meters (10 to 26 feet). Multipath reflections from buildings are the main culprit here. Dual-frequency L5 signals handle this better than L1-only receivers, which is one reason newer phones perform noticeably better in cities.

- Dense forest canopy: 5 to 15 meters (16 to 50 feet). Heavy foliage attenuates satellite signals and limits the number of satellites your phone can track. This is the most challenging common environment for any GPS receiver, consumer or professional.

- Indoor or deep urban canyon: 10 to 50+ meters, or no fix at all. GPS was not designed to work indoors. If you need measurements in these conditions, satellite positioning is the wrong tool.

An important caveat: these numbers represent horizontal accuracy (the CEP95 or 95th-percentile circular error). This means that 95% of the time, your reported position will be within the stated distance of your true position. The other 5% of fixes can be worse. Vertical (altitude) accuracy is typically 1.5 to 3 times worse than horizontal accuracy due to satellite geometry.

Another caveat: accuracy varies over time at the same location. Satellite geometry changes as satellites orbit, atmospheric conditions shift, and multipath patterns evolve. A measurement that shows 2-meter accuracy at 10 AM might show 4 meters at 3 PM. This is normal and is why averaging multiple measurements or walking a boundary more than once improves results.

iPhone vs Android GPS Comparison

Side-by-side GPS accuracy demonstration on modern smartphones

This is a question that comes up constantly. The practical answer may surprise you: for land measurement purposes, the difference is smaller than the internet debate suggests.

Android's advantage: raw GNSS access. Since Android 7.0 (2016), apps can access raw GNSS measurements including pseudoranges, carrier phase, and Doppler shift. This allows specialized apps to apply their own positioning algorithms, potentially achieving better accuracy than the default Android location service. Some Android apps and external processing tools have demonstrated sub-meter accuracy using carrier-phase smoothing on raw measurements from phones.

Apple's approach: curated positioning. Apple does not expose raw GNSS data to apps. Instead, iOS provides a processed location through Core Location, which applies Apple's own sensor fusion algorithms. Developers get a latitude, longitude, altitude, and an estimated accuracy radius. The upside is consistency: Apple's algorithms are well-optimized and produce reliable results across their device lineup. The downside is that apps cannot apply custom GNSS processing to squeeze out extra precision.

Practical accuracy difference. In real-world side-by-side testing, current-generation iPhones and flagship Android devices produce very similar results for standard location tracking. Both use dual-frequency L1+L5 chipsets, both track the same satellite constellations, and both apply sophisticated filtering. When you are walking a field boundary with a measurement app like LandLens on an iPhone or using a comparable app on Android, the position accuracy you experience is largely determined by environmental conditions (sky view, multipath, atmospheric state) rather than the phone's brand. The difference between devices is typically smaller than the variation caused by taking the same measurement at different times of day.

Where Android can pull ahead is in specialized use cases where raw GNSS processing matters, like post-processing carrier phase data or using custom RTK corrections. For general-purpose land measurement by walking a perimeter or placing pins on a map, the platforms are functionally equivalent.

Phone GPS vs Dedicated GPS Handhelds vs RTK/Survey Grade

How does phone GPS stack up against purpose-built equipment? Here is a realistic comparison.

Smartphone GPS (iPhone, Android flagship) - $0 to $1,200 (device cost)

- Accuracy: 1-3 meters open sky, 3-8 meters obstructed

- Pros: You already own it, always in your pocket, runs full-featured apps like LandLens with mapping, area calculation, and export formats like KML and Shapefile

- Cons: No external antenna option, accuracy varies with conditions, limited battery in cold weather

- Best for: Field measurement, property estimation, landscaping, outdoor recreation

Dedicated GPS handheld (Garmin GPSMAP, Trimble TDC series) - $200 to $2,000

- Accuracy: 1-3 meters standard, sub-meter with SBAS corrections on higher-end units

- Pros: Ruggedized, better battery life in the field, external antenna support, designed for all-day outdoor use

- Cons: Separate device to carry and maintain, often clunky software, limited app ecosystem

- Best for: Forestry, natural resource management, field data collection in harsh conditions

Sub-meter GPS (Trimble R1/R2, Eos Arrow, Bad Elf Flex) - $1,500 to $5,000

- Accuracy: 0.3-1 meter with real-time corrections (SBAS/PPP)

- Pros: Connects to phone via Bluetooth, uses phone as display, genuine sub-meter in the field

- Cons: Expensive, another device to carry and charge, requires clear sky view

- Best for: Precision agriculture, utility mapping, GIS data collection, wetland delineation

RTK/Survey-grade GNSS (Trimble R12i, Leica GS18, Topcon HiPer) - $8,000 to $25,000+

- Accuracy: 1-2 centimeters horizontal, 2-3 centimeters vertical

- Pros: Centimeter-level precision, legally defensible measurements, tilt compensation on newer models

- Cons: Very expensive, requires training, base station or RTK network subscription, specialized software

- Best for: Legal boundary surveys, construction layout, precision grading, subdivision platting

The key takeaway: the gap between phone GPS and survey grade is roughly two orders of magnitude (meters vs centimeters). But for the vast majority of practical land measurement tasks, meter-level accuracy is more than sufficient, and your phone delivers that for free.

Factors That Affect GPS Accuracy

Understanding what degrades accuracy helps you avoid the worst conditions and get better measurements. Here are the major factors.

Multipath Reflection

When satellite signals bounce off buildings, vehicles, water, or terrain before reaching your phone's antenna, the reflected signal travels a longer path than the direct signal. Your phone may use this delayed signal in its position calculation, introducing error. Multipath is the dominant error source in urban and suburban environments. Dual-frequency L5 signals are more resistant to multipath than L1, which is why newer phones perform better near structures.

Atmospheric Delay

Satellite signals pass through the ionosphere (50-1,000 km altitude) and troposphere (0-12 km altitude) on their way to your phone. Both layers slow the signal slightly, and the amount of delay varies with solar activity, weather, time of day, and your latitude. The ionosphere is the larger source of error and varies more rapidly. Dual-frequency receivers largely eliminate ionospheric error by comparing the L1 and L5 signals, which are delayed by different amounts. Tropospheric delay is harder to correct but is relatively stable and contributes less total error.

Satellite Geometry (PDOP)

If all the satellites your phone can see are clustered in one part of the sky, the position solution becomes less precise. This is quantified by a metric called PDOP (Position Dilution of Precision). A PDOP of 1-2 is excellent. Above 5 is poor. Above 8 means your fix may be unreliable. You cannot control satellite geometry directly, but you can improve it by choosing locations with a wider sky view. In practice, with four full GNSS constellations available, poor geometry is less common than it was in the GPS-only era. Most of the time, enough well-distributed satellites are visible.

Device Hardware

Not all phone GNSS chipsets are equal. Flagship phones from Apple (iPhone 14 and later) and major Android manufacturers (using Qualcomm Snapdragon or Samsung Exynos processors) include high-quality dual-frequency GNSS receivers. Older phones or budget models may still use single-frequency L1-only chipsets, which are more affected by ionospheric error and multipath. The antenna design also matters: larger phones and tablets generally have slightly more capable antennas than compact devices.

Phone Case Material

This is a factor most people overlook. Thick cases, especially those with metal plates for magnetic mounts or built-in batteries, can attenuate GPS signals. In testing, some heavy-duty metal-backed cases have degraded accuracy by 1-3 meters compared to a bare phone. If you are doing field measurements and want the best accuracy, remove metal-heavy cases or at minimum avoid cases with metal plates near the top of the phone where the GNSS antenna is typically located.

Motion and Speed

Standing still allows the phone to average multiple fixes and converge on a more accurate position. Moving introduces noise. At walking speed (3-5 km/h), the effect is minimal. At driving speed, the Kalman filter in the phone's GNSS processor is optimized for vehicle-like dynamics and generally performs well. But rapid changes in direction or speed can momentarily confuse the filter. For land measurement, walking steadily and pausing briefly at key points (corners, boundary features) gives the best results.

How to Maximize GPS Accuracy on Your Phone

These are practical, field-tested techniques that make a real difference. Each one addresses a specific error source.

- Choose open-sky conditions whenever possible. This reduces multipath and ensures maximum satellite visibility. Even moving 5-10 meters away from a building or tree line can meaningfully improve your fix. If you must measure near structures, place pins manually using the satellite imagery on the map rather than relying on live GPS for those points.

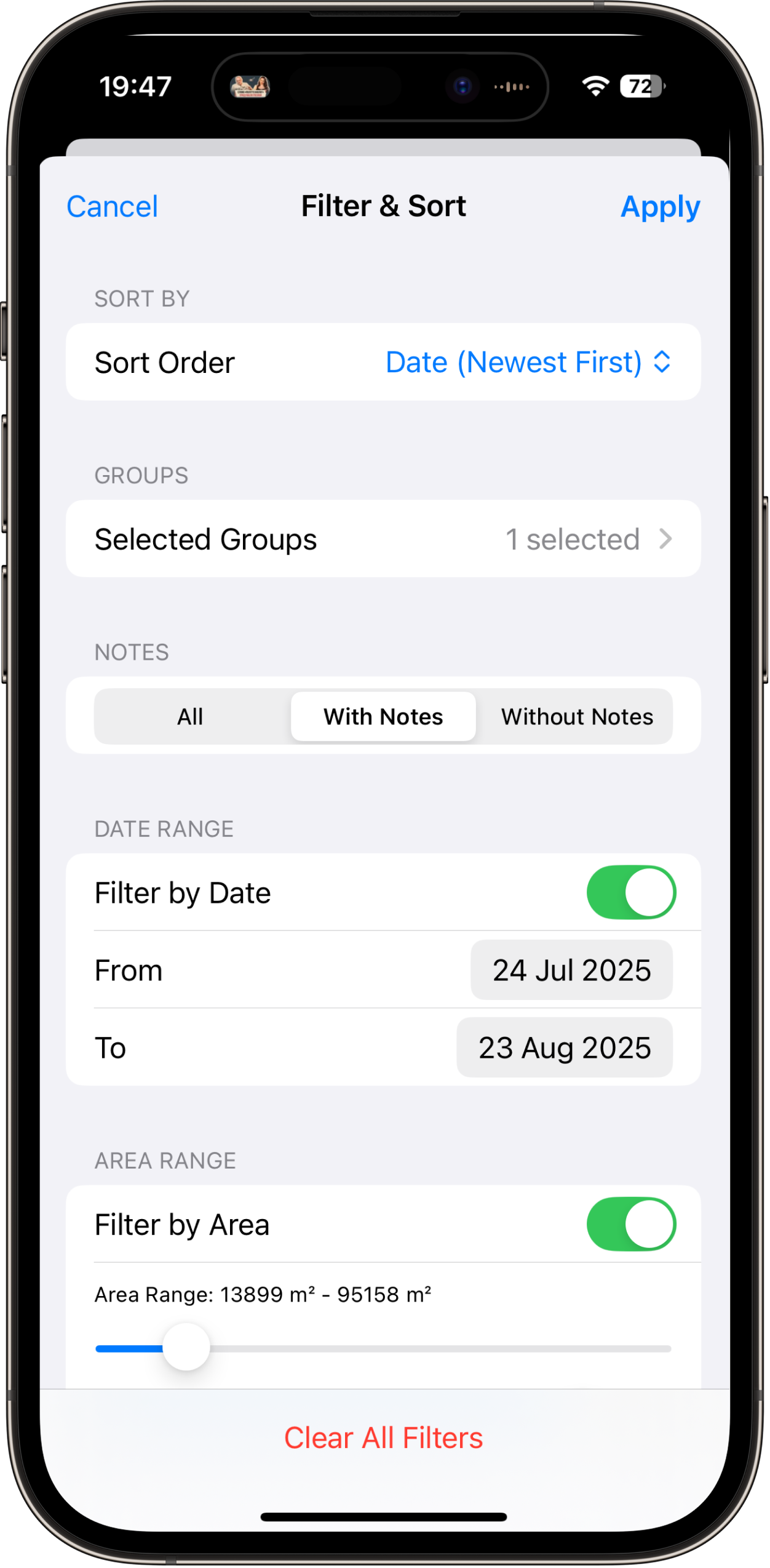

- Let the GPS settle before placing points. When you arrive at a corner or key position, stand still for 5-10 seconds before recording the point. This lets the phone average multiple fixes and refine its position estimate. LandLens shows a GPS accuracy indicator so you can watch the precision improve in real time.

- Remove metal cases. If your case has a metal plate or metal backing, take it off while measuring. This is one of the simplest ways to eliminate an avoidable accuracy penalty.

- Hold the phone at chest height, screen facing up. The GNSS antenna is typically at the top edge of the phone. Holding it vertically at chest height gives the antenna the best sky view. Putting the phone in a pants pocket or holding it low cuts off some satellite signals.

- Enable precise location in your phone settings. On iPhone, make sure Location Services is set to "Precise" for LandLens (Settings > Privacy > Location Services > LandLens). On Android, use "High accuracy" location mode, which combines GPS, Wi-Fi, and mobile networks.

- Wait for a good satellite lock after arriving on site. GPS accuracy typically improves over the first 30-60 seconds after you arrive at a new location and open a GPS-using app. The phone needs time to acquire ephemeris data from newly visible satellites and stabilize its position filter.

- Measure larger areas by walking the perimeter. For fields of half an acre or more, GPS tracking mode (recording points as you walk) tends to produce better area calculations than placing individual pins. This is because walking produces many points, and random errors at individual points tend to average out over the full perimeter. Some points will be slightly inside the true boundary, others slightly outside, and the area calculation ends up close to correct.

- Measure the same area twice and compare. If the two measurements are within 2-3% of each other, you have a reliable result. If they differ by more than 5%, conditions may be poor, and you should try again at a different time of day.

- Check the time of day. Satellite geometry changes throughout the day as satellites orbit. In some locations, there are predictable windows of better and worse geometry. If you get a poor result, trying again 2-4 hours later with different satellite positions may help.

When Phone GPS Accuracy Is Sufficient

For most practical land measurement tasks, meter-level accuracy is more than adequate. Here are the common use cases where your phone delivers genuinely useful results.

Agriculture and farming. When you need to know your field sizes for fertilizer calculations, seed rates, or chemical application, 1-3% accuracy in area measurement is excellent. A farmer measuring a 40-acre field with phone GPS will get a result within half an acre of the true value. That is close enough for purchasing inputs and reporting to crop insurance. Many farmers use LandLens to map all their fields, organize them in folders by farm, and reference the measurements season after season.

Landscaping and property maintenance. Whether you are ordering sod, estimating mulch volume, or quoting a mowing contract, you need to measure land area with your phone quickly and get a working number. A 3-meter accuracy margin has negligible impact on a 10,000-square-foot lawn measurement. It is certainly more accurate than eyeballing it or pacing it off.

Property estimation and real estate. Checking whether a listing's stated acreage matches reality, evaluating a potential purchase, or comparing parcels. If the listing says 5 acres and your phone measurement says 4.2 acres, that is a meaningful discrepancy worth investigating further. Phone GPS is excellent for this kind of verification and sanity-checking.

Outdoor recreation. Mapping trails, measuring plots for hunting camp planning, documenting food plots, or tracking hiking distances. These applications have no regulatory accuracy requirement, and phone GPS provides more than enough precision.

Preliminary project planning. Before committing to the expense of a professional survey, measuring an area with your phone gives you working numbers for budgeting, design concepts, and feasibility studies. Many people use phone measurements to decide whether a project is worth pursuing before investing in a formal survey.

Government programs with approximate measurement. Some agricultural subsidy programs and conservation programs accept farmer-reported field measurements that do not require survey-grade precision. Phone GPS measurements with a documented methodology can serve this purpose.

When You Need Better Than Phone GPS

Honesty about limitations is important. Here are the situations where phone GPS will not meet the requirements, and you need professional equipment or services.

Legal boundary surveys. When property boundaries will be recorded in a legal document, deed, or plat, you need a licensed surveyor with RTK or total station equipment. Phone GPS measurements have no legal standing in boundary disputes, property transfers, or land division. Courts require surveys performed by licensed professionals using instruments with documented, traceable accuracy.

Construction layout and grading. Setting building foundations, grading roads, installing drainage systems, and laying utilities all require centimeter-level positioning. A 2-meter error in a foundation layout would be catastrophic. Construction GPS (machine control systems) uses RTK corrections to achieve the 1-2 cm accuracy these applications demand.

Precision agriculture. While phone GPS is fine for measuring field boundaries and estimating acreage, variable-rate application (applying different amounts of seed, fertilizer, or chemicals to different parts of a field based on soil maps) requires the sub-meter or centimeter-level accuracy that RTK-equipped tractors and application equipment provide. The field boundary measurement and the precision application are different tasks with different accuracy needs.

Subdivision platting. Dividing a parcel into lots for development requires centimeter-accuracy corner positions that will be legally recorded and used as the basis for property ownership. This is fundamental survey work.

Engineering and scientific measurement. Monitoring land subsidence, tracking erosion, measuring structural movement, or establishing control networks all require accuracies that are orders of magnitude better than consumer GPS.

Testing GPS Accuracy Yourself

Do not take anyone's word for it, including ours. Here are practical ways to evaluate your phone's GPS accuracy for your specific conditions.

Walk a known area. Find a location where you know the precise dimensions: a sports field, a surveyed property with known acreage, or a parking lot with painted dimensions. Measure it with your phone and compare your result to the known value. A regulation football field (between goal lines) is 100 yards by 53 1/3 yards (1.32 acres). A high school running track's inner oval is typically 400 meters. These are free, publicly accessible calibration areas.

Compare with official records. If you know your property's surveyed acreage from a deed or plat, measure it with your phone and compare. Walk the entire perimeter and use the GPS tracking mode for the most complete boundary capture. The percentage difference between your phone measurement and the surveyed value gives you a direct indication of practical accuracy for your specific location and conditions.

Measure the same area multiple times. Walk the boundary of an area three or more times on different days or at different times of day. Calculate the mean and the spread of your results. If all three measurements are within 2% of each other, your conditions are good and your phone is performing well. If there is a 10% spread, something is affecting accuracy (probably tree cover or buildings) and you should adjust your technique.

Check the accuracy indicator. LandLens displays the GPS accuracy reported by the device. Watch this number as you move around your measurement area. If it stays at 3 meters or better throughout, you can be confident in the result. If it spikes to 10-15 meters in certain spots, those points will be less reliable, and you might want to place pins manually using satellite imagery in those areas instead.

Use satellite imagery as a cross-check. After completing a GPS-tracked measurement, zoom into the satellite view in the app and compare your recorded boundary with what you can see in the imagery. Do the recorded points line up with the visible fence line, tree row, or road edge? If they are systematically offset, that tells you about the accuracy at that time. If they align closely, your measurement is solid.

The Bottom Line

In 2026, the GPS in your phone is the most capable consumer positioning system ever built. Dual-frequency reception, multi-constellation tracking, and sophisticated processing deliver 1-3 meter accuracy in good conditions. That is a remarkable engineering achievement available in a device you already carry.

For the vast majority of practical land measurement needs, from farming to landscaping to real estate verification to project planning, phone GPS gives you reliable, actionable numbers. LandLens is built to get the best possible accuracy from your iPhone or iPad's GPS hardware, with real-time accuracy indicators, manual point adjustment, multiple measurement modes, and the ability to export your data in professional formats.

The key is matching your tool to your task. Need a working number for planning, purchasing, or estimating? Your phone handles it. Need a legally binding measurement for a deed, subdivision, or construction project? Call a licensed surveyor. Knowing which situation you are in is half the battle.

Try LandLens free

Measure any land area, distance, or perimeter with your iPhone or iPad. No equipment needed.

Download on the App StoreShare Your Feedback

Help us build a better LandLens. Request features, report bugs, or tell us what you think.